Guidance

Planning permission for barn conversions

The re-use and adaptation of existing rural buildings can reduce demands for new buildings in the countryside, avoid leaving existing buildings vacant and prone to vandalism and dereliction, and provide jobs or housing.

Non-residential uses would normally be preferable as they can provide more employment opportunities and might not require extensive alteration - if the building is to be used for storage or industrial purposes, for example, it might not need large window openings usually associated with residential use and there is not a need for domestic gardens, which can have a detrimental effect on rural character.

Planning applications for the conversion of buildings to residential use in the countryside will be examined with particular care to ensure that the conversion does not affect the rural character of the building or the character of its setting.

Buildings suitable for conversion

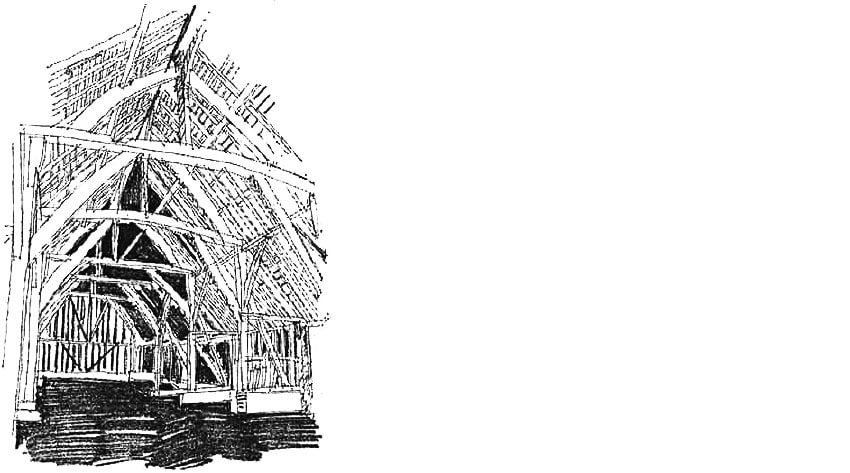

In considering whether a building is suitable for residential conversion, we will consider whether its form, bulk and general design is in keeping with its surroundings. Generally larger, more modern agricultural buildings would not be considered appropriate for residential conversion because they are often of a size and design that is not in keeping with their surroundings.

Generally, modern agricultural buildings are of portal frame construction with blockwork walls. Often the pitch of the roof is too low to use traditional plain tiles, which are the local vernacular building material.

More modern agricultural buildings are not domestic in scale and the alterations necessary to insert windows and doors into buildings constructed of blockwork and portal frame, together with the raising of the roof to accommodate clay or concrete tiles would constitute extensive alteration, which would have a harmful effect on the character of the countryside.

There are, however, a range of more traditional buildings (including some modern structures) which would be considered more suitable for residential conversions. These include brick and tile buildings such as former stable buildings, bothys and traditional timber-framed buildings.

We are committed to maintaining or enhancing the character of the countryside and therefore any residential conversion of an agricultural or other rural building will normally only be permitted where it retains the rural character of the building and its setting.

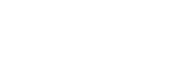

Traditional timber-framed buildings

Many traditional timber-framed barns possess both architectural and historic interest. A number of them have been built in the 16th and 17th centuries and are either listed buildings or of listable quality.

In the case of such buildings, we would have to be convinced that a residential conversion could retain both the external and internal character. The roof structures are often of high quality and architectural interest, for instance incorporating King or Queen posts. Where this is the case, we would expect some of the roof structure to be open to view (even if the space is sub-divided). In order to preserve at least part of the interior character of the building, a suitable proportion - normally at least one third of the space - must be left open from ground level to the ridge.

Often interior heights to wall plate or tie beam levels are too restricted to allow for two floors. The use of split staircases and galleries can overcome this problem whilst giving existing interiors considerable character and interest.

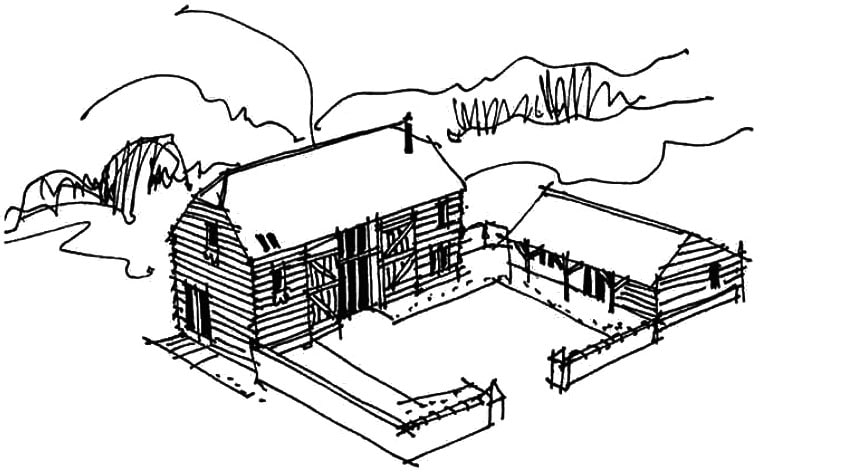

To reduce the level of sub-division of the main barn, we would, in some circumstances, accept small extensions, particularly where they facilitate the use of adjoining single-storey cart sheds.

Low cart sheds and other ancillary buildings attached to barns often lend themselves very well to conversion and sub-division to smaller rooms.

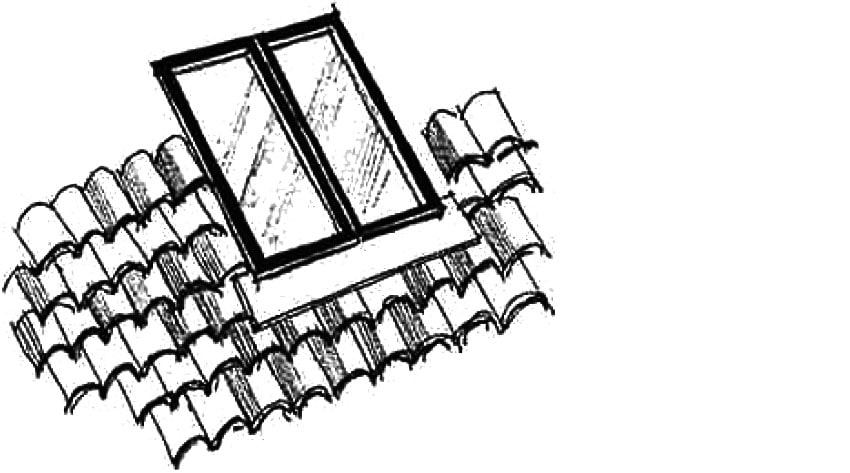

Roofs and dormer windows

The roofs of traditional rural buildings are steeply pitched and often clad in handmade clay tiles. These features should be uninterrupted visually.

The introduction of dormer windows and/or large rooflights will usually be resisted. A limited number of small conservation rooflights, which are flush with the tiles, can be an appropriate method of providing light to first floor accommodation.

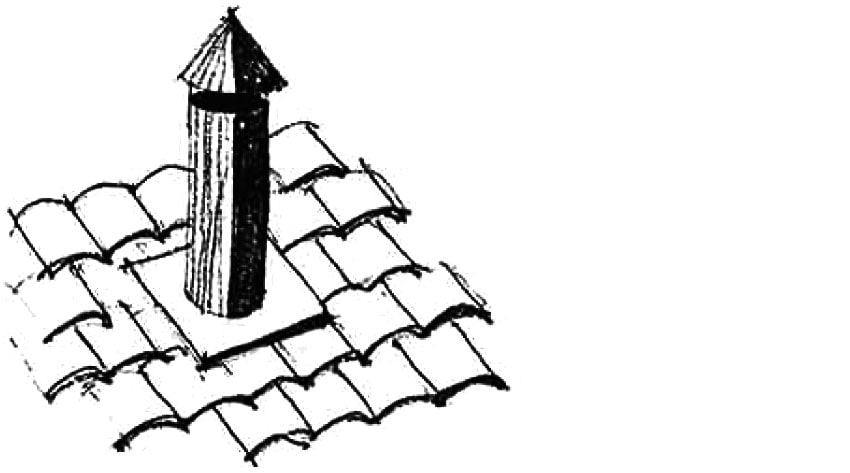

Brick chimneys, which are very domestic features, will be resisted.

Where appropriate, on timber-framed barns, steel flues painted black would be considered an acceptable alternative.

Exterior walls

The most effective way of providing light to the main barn is to utilise the cart entrances.

Barn doors can be retained as shutters since they will normally fold flat against flank walls. Glazing can be inserted to provide light to flanking areas as well as direct into the building. This also helps to 'hide' the glazing. The insertion of windows can greatly change the character of the building. Generally, windows should be small, vertical in emphasis and inserted in a random fashion to avoid a domestic appearance.

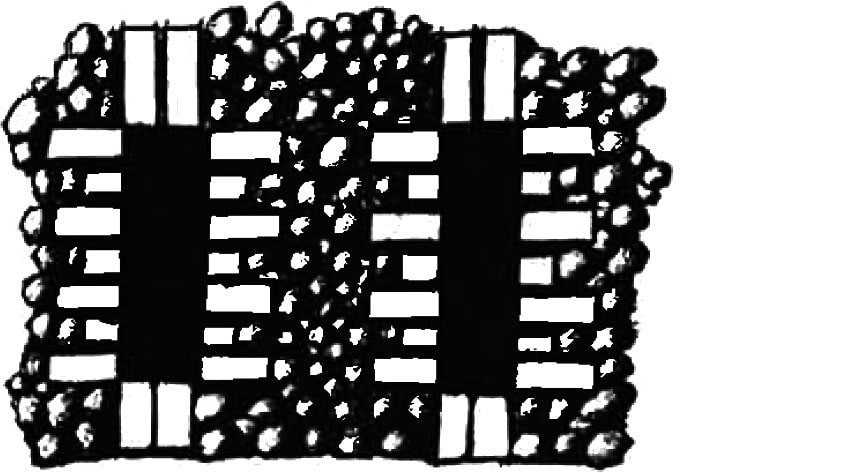

Existing features such as ventilation slits, patterned brick and flintwork should be preserved unaltered in any conversion scheme.

Other rural buildings

The principles relating to the conversion of timber-framed barns also apply to the conversion of other rural buildings. Generally the aim should be to keep the number of external alterations (such as new windows and doors) to a minimum, utilising existing openings and preserving the rural character of the building and its landscape setting. By avoiding a 'domestic' appearance to rural buildings, the undeveloped rural character of the countryside can be retained.

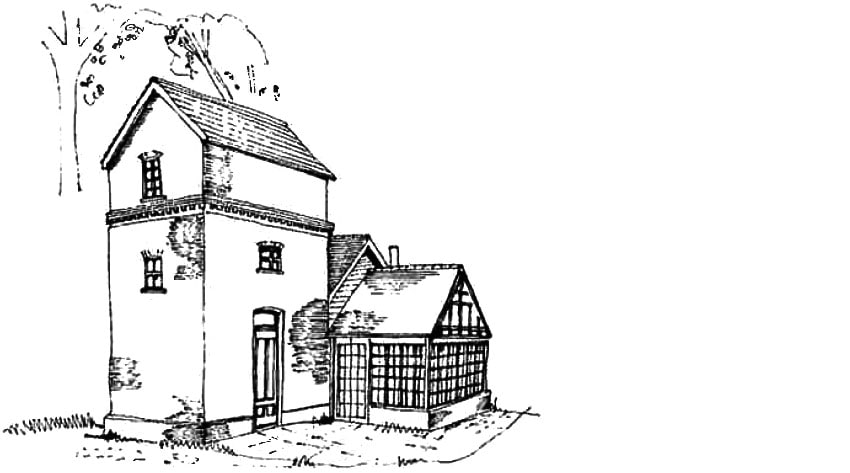

Many traditionally constructed buildings such as brick and tile stables, bothys and water towers can be sympathetically converted, retaining existing openings.

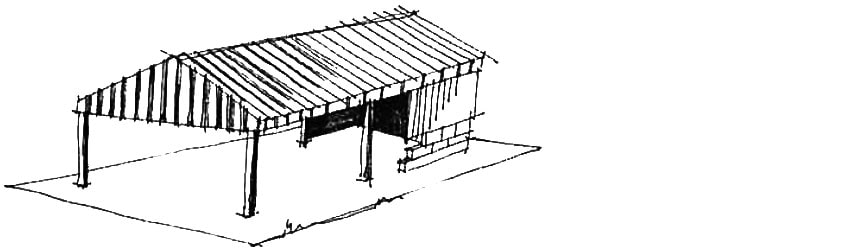

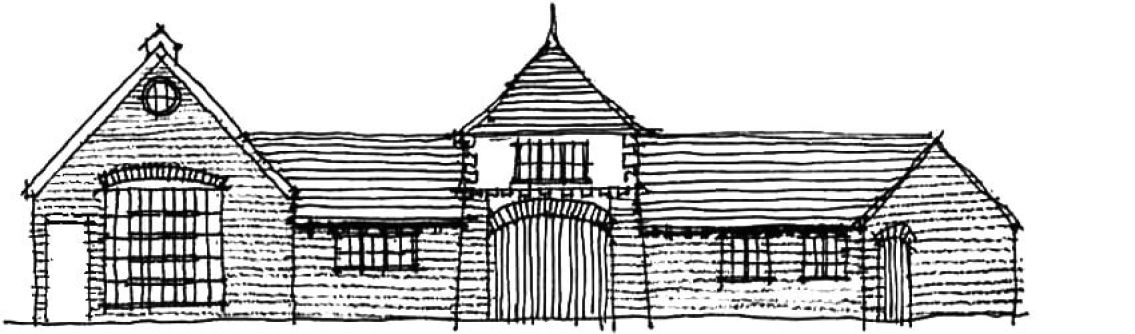

An example of a successful rural building conversion

Residential curtilage

However well a scheme for conversion is carried out in terms of the preservation of the character of the building, the creation of a residential curtilage can significantly harm the rural setting of the building.

As a general rule, the residential curtilage should be kept small and adjacent to the building using existing hardstanding areas around buildings. Garaging and storage provision should be made within existing outbuildings and we will normally impose conditions removing permitted development rights for ancillary buildings such as additional garages, sheds and other outbuildings.

Alterations and repair

Planning permission will normally be refused for any conversion that results in extensive alteration or substantial reconstruction in order to bring them into residential use. Where we are in any doubt as to whether a building can be suitably converted, the applicant will be required to submit a structural survey and/or a method statement setting out how it is intended to convert the building without significant extension and/or rebuilding.

In determining whether the amount of rebuilding is acceptable, a distinction will be made between structure and/or cladding or infill. While it is essential to retain or re-use as much as possible of the original, the renewal of cladding such as weatherboarding or tiles will not normally be counted as rebuilding provided the traditional materials, details and finishes similar to the original are used as replacements. In the same way, there will be a distinction between principal and secondary timbers on timber-framed barns with the retention of important principal rafters, wallplates and main posts being more important than the latter common rafters and studs.

In considering what element of re-building is acceptable, we will consider each case on its merits. However, as a general rule any proposal which involves a new roof structure of re-building of any significant section of walling (ie a gable end) would normally be regarded as unacceptable.

Subsequent extensions to converted barns

Permitted development rights will be removed to control the design of any subsequent alteration or extension of the building. In such cases there will be a general presumption against extensions unless we are satisfied that the extension is small in scale and does not affect the rural character of the building or its setting. Generally, extensions that exceed what could be built under permitted development rights will be resisted as they are likely to be of a sale that alters the original form and design of the converted building.